The period from the mid-1840s to circa 1900 saw the publication of no fewer than forty-eight tutors for the

English concertina.1

And among the hundreds of exercises (a conservative estimate) included in these manuals,

there is hardly a better one for building technique in single-note playing than that which appears under the

rubric “Regondi's Golden Exercise” in “Signor” James Alsepti’s The Modern English Concertina Method,

published by Lachenal c. 1895.2

Before turning to the “Golden Exercise,” though, we should say something about the somewhat shadowy Signor Alsepti

himself, about whom the following biographical details, if not widely known, have long been available (and see

Postscript):

(1) he was, as he tells us in the Method (p.38), a pupil of Giulio Regondi, from whom he learned the

“Golden Exercise” directly; (2) in 1885, at which time he resided at 6 Mount Pleasant Road, Exeter, Alsepti and

Richard Ballinger, the latter an employee of the firm of Lachenal, received a

patent for the invention of their

so-called “bowing valves” (called “relief” valves in the patent), which, situated near the thumb strap on each

side of the instrument and raised and lowered with the thumb (thus operated somewhat like the modern air valve),

were supposed to permit subtle gradations with respect to both dynamic levels and the manipulation of the bellows

(Alsepti likened the latter feature to the use of the bow on string

instruments);3 and (3) by the late 1880s, he

had become something of the “house” concertinist for the publishers and instrument dealers Keith, Prowse, who

describe his activities as follows in an advertisement of 1888 in which they pitch the virtues of Alsepti's “

several great improvements” to the English

concertina:4

[Click on advert for a larger image; near the bottom it reads:]

“SIGNOR ALSEPTI (Pupil of the late Giulio Regondi) has been performing at Balls

and playing solo parts at Concerts, to the unbounded delight of his audiences.

Signor Alsepti GIVES LESSONS at 48, Cheapside, where also he can be HEARD

PERFORMING DAILY on the CONCERTINA ALONE, and with PIANOFORTE accompaniment.

Ladies and Gentlemen desirous of hearing these delightful and almost phenomenal

performances will be admitted on presentation of their Cards at 48, Cheapside.

Signor Alsepti can be ENGAGED for CONCERTS, DANCES, &c., on application to

Keith, Prowse & Co., 48, Cheapside.”

Yet despite the “unbounded delight” of his audiences, Alsepti's reputation may have been somewhat more limited

than Keith, Prowse would have us believe, for a search through the indices of Victorian music journals currently

being issued by the Répertoire International de la Presse Musicale

(RIPM) failed to turn up even a single citation

to him.5

Finally, the name “Alsepti” itself raises a question: is it a real

Italian name, or is it, in combination with the

use of “Signor” in front of it, merely part of a facade? Was Alsepti simply posing as an Italian? The answers to

the three queries seem to be no, yes, and yes, respectively. First, the name does not appear in Emidio De

Felice's authoritative

Dizionario dei cognomi italiani;6

and while De Felice's work makes no claim to being

exhaustive (it contains just under 15,000 entries), the name is also absent

from L'Italia dei cognomi/Surnames in

Italy, which offers a data base of twenty million entries drawn from local Italian telephone

books.7

In all, the

name simply fails to ring true.

We can, however, do more than argue negatively from the silence of the two Italian data bases, for thanks to

records preserved at the Devon Record Office, we can shed further light on the matter and also add some new

tidbits to Alsepti's biography.8

- He is already recorded as residing at 6 Mt. Pleasant Road (St. Sidwell parish) in the 1881 Exeter census,

where he is listed—in the transcribed index—as James “Alseph” (surely an incorrect rendering of “Alsepti,” as the

original “-ti” is easily enough misread as “-h” if the dot over the “i” and the cross of the “t” are less than

tidy and run into one another); in addition, he is said to be forty-four years old, born in Exeter, a “Professor,”

and husband of Bessie “Alseph” (age forty-six and born in Middlesex).

- The same census index also contains an entry for Ellen “Alsept,” eleven years old, also born in Devon,

resident in the same St. Sidwell parish as our concertinist, and living in the household of one Agnes Bolt. Could

Ellen be related? Since she is living in another household, it seems unlikely that she would be the Alsepti's

daughter, but we cannot rule out the possibility that she might be a niece. Moreover, it seems unlikely that “

Alsept” is a misreading.

- The transcribed index of the 1851 Exeter census (thus thirty years earlier) also has what must certainly be

an entry for our concertinist, this time as James “Alsept,” resident at 27 John Street, age fifteen, living with

his parents, and already listed as a musician. His father is also named James “Alsept,” age forty-three, a

tailor, born in Cheriton Bishop (Devon); his mother is Ann “Alsept,” age forty-seven, employed as a charwoman, and

born in Exeter; in addition, there is a brother, John T. “Alsept,” age five, as well as two babies with different

surnames who are recorded as “visitors” (foster children).

- The Cheriton Bishop Church of England baptismal register contains an enticing entry: one James “Alsop,” son

of Robert and Agnes Alsop, was baptized on 30 October 1806. Could this refer to

James “Alsept,” senior, father of

the concertinist, with whose age as recorded in the 1851 census—taken on 30 March of that

year—the date of

baptism squares perfectly?

In all, the four notices seem to tell us the following: (1) “Signor Alsepti” was born at Exeter in either 1836 or

1837, either year fitting nicely with his having been listed as fifteen and forty-four years old in the 1851 and

1881 census schedules, respectively (see Postscript); (2) “Alsepti” was almost certainly not his real name; more

likely, the family name was “Alsept,” which, since that name appears in the indices of the schedules for both 1881

(in connection with Ellen) and 1851 (in connection with both the concertinist and his family), is unlikely to be

either an error in the original schedules or a misreading on the part of a transcriber (as students of “textual

criticism” would put it: it is unlikely that two different schedules, separated by thirty years, would have made

the same error; nor is it likely that the transcriber(s) of the indices would land upon the same incorrect name

coincidentally with one another, or, if only one transcriber is involved, on two different occasions); and (3) it

is possible that “Alsept” itself was a spin-off of Alsop.

Finally, we might speculate about why the Exeter-born James Alsept erected his Italianate facade in the first

place. No doubt, he was trying to cash in on what seems to have been a then-current (at least in some

circles)—if rather off-the-mark—association

between the English concertina, on the one hand, and Italians, on the other.

After all, during the years in which the young concertinist was cutting his teeth on the instrument, it was Giulio

Regondi—probably born at

Genoa9—who reigned

supreme on the instrument. And if that were not enough to fuel such

an association, we may thank the novelist Wilkie Collins for stoking the flames: in his spectacularly

popular The

Woman in White (1860), Collins puts the instrument into the hands of the Italian Count Fosco—he plays a

transcription of the famous “Largo al factotum” from

Rossini's The Barber of Seville—surely the best-known and

most highly cultivated villain in Victorian literature. Collins, too, it seems was riding the Regondi

phenomenon.10

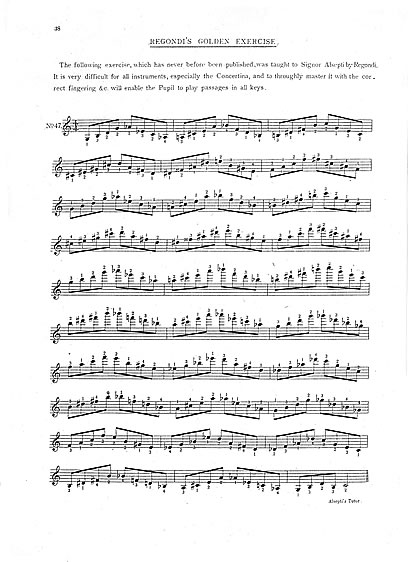

To turn to “Regondi's Golden Exercise” (see

Example 1 at the end of the essay): Alsepti (to use his preferred version

of the name) offers it with the following note of explanation:

“The following exercise, which has never before been published, was taught to Signor Alsepti by

Regondi. It is

very difficult for all instruments, especially the Concertina, and to th[o]roughly master it with the correct

fingering &c. will enable the Pupil to play passages in all keys.” (Method, 38.)

What is it that makes the exercise so valuable? There are three features that stand out: (1) the chromaticism,

as each arpeggio is answered immediately by one that is first a half-step higher and then, upon turning around at

measure 16, a half-step lower; (2) the rapid alternation between ascending and descending patterns; and (3) the

need to take full advantage of the English concertina's enharmonic tones (see below). In all, the exercise keeps

us somewhat off balance, as it avoids the mechanical and repetitive patterns of one- note-in-one-hand/one-note-in

-the-other-hand that tend to fall almost mindlessly beneath the fingers when playing in keys with but a few sharps

or flats. And indeed, most of the exercises in tutors for the English concertina—whether from the Victorian

period or our own—suffer from an acute case of

“C-majorism.”11

Yet despite its praiseworthy features, the exercise, at least as offered by Alsepti, presents most of us with a

major problem. Like Regondi and a number of other Victorian concertinists, Alsepti was a proponent of playing

with four fingers of each hand, and his fingering calls for the fourth finger (the pinky) thirty-seven times. As

he puts it in the section “On Holding the Concertina” (Method, p. 7; the

italics in both this quotation and the

next are Alsepti's):

“As the fourth finger of each hand is to be used as frequently as the other fingers, the

pupil should never use the metal plates. . .as a rest for that finger. These rests are only useful as a guide.”

He continues (p. 7):

“The first finger of each hand must cover the first (or top [that is, nearest the thumb

strap]) row of keys,

the second fingers must be held over the second row.

The third fingers over the third row,

and the fourth fingers over the fourth (or lowest) row of

keys … .” 12

The problem, of course, is this: most present-day players of the “English” (myself included) use only three

fingers of each hand, as we keep the fourth finger planted in the finger rest in order to help balance and support

the instrument. We must, therefore, do some surgery on Alsepti's fingering, and I have done precisely that in

Example 2, which appears at the end of the essay.

Unlike Alsepti, I have not fingered every note, as there are stretches during which the fingering should be

perfectly self-evident. I have, however, entered fingerings for all instances in which there is a choice between

the enharmonic notes D♯/E♭ and G♯/A♭, adding an asterisk in those instances in which, for instance, I suggest

that a G♯ be played instead of a notated A♭. In addition, I have signaled the obvious use

of F (natural) and G (natural) for E♯ and

Fx (double sharp), respectively,

simply as a reminder to those who seldom venture into keys that require such

enharmonics.

Now, fingering is a very personal thing: what one player finds comfortable, another finds downright

clumsy.13 I

should, however, “justify” what I have done. Briefly, my bottom-line rules-of-thumb (and they are nothing more

than that) for fingering are these: (1) avoid using the same finger on two successive notes (this is the “rule”

that most of us are least likely to break); (2) avoid, if possible, using adjacent fingers—whether 1-2 or

2-3—successively if they must skip over a vertical row (I find the fork-in-the-road-like lateral stretch

uncomfortable); and (3) try to divide the work between the two hands as evenly as possible. Thus it is the

combination of these last two guidelines that led me to use RH 1 and the

enharmonic g♯ (in place of the notated

a♭) at the end of measure 1, as this gets around

the problem of having to play six successive notes in LH and

having to use LH 2-1 on a-c♯' .

Otherwise, virtually everything having to do with fingering (and now my remarks go beyond just “Regondi's Golden

Exercise”) depends upon

context: (1) phrasing and articulation (are we playing legato or with some degree of

detachment, and are we going to articulate a pair of reiterated notes by playing them twice with the same finger,

or by changing fingers on them, or by keeping the button depressed and changing the direction of the bellows?);

(2) tempo (simply put, one can “cheat” at a slow tempo); (3) direction of the bellows (I find some fingerings more

comfortable with the bellows going in one direction than in the other, though this may well be a purely personal

idiosyncracy); (4) depth of thumb in thumb strap (because I place my thumbs in the straps as far as they will go

and keep the straps rather tight—the better to control the bellows, at least to my way of

thinking—I am often

uncomfortable using RH 1 on the low g and,

in some contexts, on the d' right above it; thus I often use RH 2 on

these notes, and sometimes even bring RH 3 across for the g);

(5) strength of individual fingers (for example, I

always try to play trills in the same hand with 1-2, no matter which rows the notes may be in); and most important

(6) where are we coming from and where are going? This last question is paramount, and it often leads to

fingering the same passage in different ways depending upon what comes immediately before and after. A good

example of this in my fingering for the “Golden Exercise” occurs in measures 15-16, where I suggest two different

fingerings for two ascending B-major arpeggios.

In the end, “Regondi's Golden Exercise” makes us think: about ourselves as players and about the capabilities and

idiosyncracies of the English concertina. And only when we have thought about both of these matters long and

hard, do we and the instrument truly become one.

Postscript

Shortly after submitting this essay, I had occasion to speak to Douglas Rogers, who kindly reminded me

of two other pieces of biographical information concerning Alsepti: According to an article that appeared in the

Pall Mall Gazette for 2 February 1889, Alsepti (1) was blind and wore dark spectacles; (2) belonged to the

Franciscan Brothers;

(3) performed Beethoven's “Kreutzer”

Sonata;14

(4) had spent time concertizing and giving lessons in the industrial

north; (5) was still associated with Keith, Prowse (see the 1888 advertisement cited above); and (6) had been

successful in passing himself off both as an Italian and as the inheritor of the Regondi legacy.

Finally, Alsepti's death certificate, registered on 9 March 1897 in the district of Greenwich (subdistrict

Deptford South), states that Alsepti, a “Professor” of music, died the previous day (8 March) of acute bronchitis

at the age of fifty-nine; at the time of his death, he was living at 107 St. John's Road. Given this statement

about his age, we can now determine his date of birth as 1837.

Needless to say, I am extremely grateful to Douglas for sharing this information with me.

Have feedback on this article?

Send it to the author.

Reprinted from the Concertina Library

http://www.concertina.com

© Copyright 2000– by Allan W. Atlas