Introduction

Although there was a substantial revival of interest in

Concertina in the final quarter of the twentieth century, perhaps

the only significant development of the instrument, over its

Victorian predecessors, was the introduction of the Hayden Duet

keyboard system. Developed by Brian Hayden in the 1960s, this

allowed the player to play in most keys with comparative ease.

Brian grew up in Rochester, Kent, a fifty minute train journey

from London, but now lives in Somerset in the South West of

England.

I had asked Brian, as an old friend and acknowledged expert on

'things concertina', if he would check through an article that

I'd written. He kindly agreed, but I thought that it would be a

good idea, at the same time, to 'interview' him about his own and

other Duet systems. We fixed a date for the 5th of April 2001,

and what follows is a transcript of our chat. I've changed a few

things to make it flow when written down, as normal conversation

doesn't, and I hope nothing has been lost.

Brian Hayden Background

WW: When did you get into concertinas? How?

BH: When I was still at school my father ran a local

Square Dance Club, I've been in 'folk' since the American Square

Dancing came in. In the year [1952]before the Coronation,

Princess Elizabeth [now Queen] went to Canada and did

American Square Dancing. That's when my father took it up,

although he was already into Scottish dancing and Old Tyme

dancing before that.

I went to an American Square Dance in Gravesend in the late

1950s. During the evening a Morris Dancing team, 'The Beaux of

London City' performed. It was the most marvellous thing I'd ever

seen in my life, these men all dancing, bells, ribbons,

handkerchiefs, and so on. I liked the music as well, which I

thought was better than the American Square Dance music. It was

the one thing I most wanted to do, but my father wouldn't let me

go and join a morris team at that time because I was still in the

middle of my GCE O levels. But before I left school I did join a

Morris Dancing team in Gravesend, whose musician was a melodeon

player called Reg Hall. Although I'd taken up playing the piano

accordion, I was quite a small boy at the time, very thin,

undersize for my age [Brian is a hefty 6 feet plus now]and

I could hardly manage this enormous great big 80 bass piano

accordion. Of course, I saw this lovely little instrument of Reg

Hall's and I thought "I'll have one of those", so I got one

eventually.

It was a G/D melodeon. I knew that G/D was the right melodeon

to have, and I went to Bell Accordions in Surbiton, Surrey to get

one because I'd been told that was the only place that did them.

The manager there was a Mr Larkin who had a very good

relationship with all the folk accordionists, and he said "Oh

yes we've got one, its the last of the second batch of ten made

in G/D. The first batch sold fairly quickly, but the second batch

hung around, and this is the very last one." But It was a

Hohner Erica, and I wanted a Hohner poker work, because that to

my mind looked more folky. He said "We're not having anymore

of these made because the second lot sold rather slowly and that

will be it. It's either this or you'll have to have one specially

made for you in the future. We're not going to deal with anymore

G/D melodeons!". Of course the number you see nowadays!!!

The following year, after I had learned a good number of

Morris tunes and a few English Country Dance tunes, I took it to

the second Sidmouth Festival [The major English Folk

Festival] - and I was the only melodeon player there!!!

Then I took it to University with me at Kings College,

Newcastle Upon Tyne. I learned clog dancing from one or two

traditional dancers who were also up there, but mostly from

Johnson Ellwood, of Chester-Le-Street, and was an active dancer

in the college Morris and Sword Dance Club.

WW: What did you study at University?

BH: Physics and Maths … AND morris dancing … AND clog

dancing … AND Rapper sword dancing … AND took up up the

Northumberland small pipes, but I never continued with them after

I left Newcastle.

After I finished there I did various things, I was a teacher

for a time, and I worked in a laboratory for a while. I ended up

in London in the mid 60s, the time that folk song was really

taking off.

Invention of the Hayden System

I used to go and and play at a club called the London Folk

Music Centre, which was extremely good, run by Karl Dallas, who

was a reporter for Melody Maker [A national weekly music

newspaper] at the time. There were a couple of folk singers

who wanted me to play for them, but I was very disinclined. I

used to play background music and would occasionally accompany

singers, and so on.

It was just before I started going there that I'd been down

Portobello Road [A London street renowned for antiques and

curios] and I spotted these two concertinas in T Ord-Hume's

second hand shop. He was a specialist in mechanical musical

instruments, but he also had harps, concertinas, accordions, and

so on. There were a couple of Jeffries anglos there and, of

course, I could have one or the other. I actually had enough

money on me to buy both, but I only bought one. It sounds mad

now, as it was only £6. I could have had both for

£10. I sold it for about £800 about ten years ago,

but now its probably worth a couple of thousand.

This concertina was in C/G and I could only play it in C, G

and a little bit in F. By now, I had an melodeon-ish thing which

I'd somewhat developed from being a basic melodeon. It had four

rows and it played in G/D/A/B flat and so I could play most keys

between the lot. It had a 48 button Stradella bass on the left,

which more or less played in any key too. Many years later it was

eventually converted into a Hayden system on the right, same note

both ways, with the Stradella bass on the left, which I was

familiar with, but it wasn't until I got a concertina that I

realised how good the Hayden bass system was.

This melodeon thing developed a bit more so it could play in

any key using the same fingering. Some of the buttons you pulled

and pushed on the same button, and other buttons you pushed on

one button and pulled on the button on the row below it. It was

very closely related to a continental chromatic but playing

different notes both ways.The singers wanted a concertina sound

because that was counted more traditional, and I could only play

for them in C and G on the concertina, but I could play them any

key they wanted on the accordion.

I spotted this Jeffries Duet when I went up to Crabbs once.

Crabbs always dealt in second hand as well as new, and I thought

"Thats what I want". In those days I thought that Jeffries was

the best make - this isn't my opinion now - but it was at that

time because everything was anglos and loud music. So I bought

it. It was in A flat and it played passably in A flat and D flat

but it really didn't play in any normal key at all easily, and I

thought "I can alter this - let's see if I can improve it", which

is what I did. I moved the reeds around, to and fro, for about a

year and I accidentally hit the right way of doing it.

I wasn't actually working on the concertina itself, but I went

away to Sidmouth with this folk singing duo - The Trunkles - one

of the first years where they actually paid the performers! As I

was crossing the road it suddenly came to me that if I arranged

the notes in a certain way the key of C and the key of F would

come up identically and then it occurred to me, with the work

with the melodeon-ish sort of thing, if two were the same, then a

lot more would be the same.

WW: This was when?

BH: The late 60's.. mmm... 1967. I went back and I

finally altered this Jeffries to this system and Bingo! it worked

and I thought the idea was right. But by then, because I'd moved

the reeds around so much in this Jeffries, I'd play a couple of

tunes and then two or three notes would fall out. [Brian later

confirmed 1967, and that the date of 1963 quoted in some articles

was incorrect]

WW: From what you've shown me of the layout of the

Jeffries Duet, it must have been easier to convert to your system

than any other system. That was a lucky break then?

BH: Well, yes. The staggering of the notes is what does

it. The scale divides into 3 and 4 notes. If its done in vertical

rows like a Maccann or an English or a Crane then you always get

an even number of notes for a scale whereas by staggering it, the

three and four - your C-D-E row of three and your F-G-A-B row of

four - just sit one on top of the other.

It was a Jeffries system I was converting, and that one was so

bad because it was in A flat, that started me altering it. A

lucky break, and I just happened to hit on the idea. Of course

the work on the melodeon things helped me find the right answer

in the end.

WW: So if you'd played Maccann, you wouldn't have

come up with this Hayden system, but perhaps something

different?

BH: I'd have probably come up with something completely

different. You've got vertical columns so you'd probably come up

with three fours or two sixes rather than the staggered three and

the four.

WW: So when was the first true Hayden system

made?

BH: I ordered it from Crabbs in 1971, but it wasn't

finished until 1976 . In fact it was the last concertina that

Harry Crabb made before he retired, so it must have been November

1976. He gave it the number 18500 as it was a 'special'. He used

to save special numbers for instruments that were different from

the normal ones. For instance, when I ordered my Hayden system

instrument from him, they were making a special instrument for an

Australian which had lots of Australian things worked into the

fretwork, like the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and so on. That would

have had a special number too. In your dating article, if you

want an instrument number that represents a true date, you should

use John Kirkpatrick's one, as that is a standard production

instrument.

WW: And now lots of the new makers are making

them.

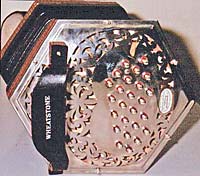

BH: Yes, Steve Dickinson makes the Wheatstone ones,

Colin and Rosalie Dipper have made them, and I've been impressed

by Robin Scard who works with Dipper Concertinas. He lives in a

nearby village to the Dippers, and has made several very nice

Hayden system concertinas. I think Rosalie made the bellows on

mine, while Colin tuned and voiced it. John Connor is also making

them, and I've just sent details to another manufacturer.

WW: How many were made by Bastari?

BH: There were forty three made in total. There were

prototypes of the four and six sided, and an eight sided

prototype which wasn't continued with as some things weren't

quite right. The prototypes weren't complete instruments, for

instance the four sided only had one set of reeds. Thirty

production models were made of the six sided, and ten of the four

sided. The four sided ones were made in a much better quality

than the six sided, and had two reeds set an octave apart which

sounded together when each note played.

WW: I've got a photo essay here on a four sided

Bastari from Bob Tedrow at Homewood.

BH: The four sided didn't sell well as concertina

players didn't think they looked like concertinas, and the

accordion players felt that they should have had more bass notes

on the left. But they were built to a much better quality, and

sounded better too. In fact only six ever sold. I have one of the

unsold ones. All the six sided ones were sold.

WW: Does that mean there are still three available

somewhere?

BH: Well, I know where the three unsold ones are. I

expect that they would still be for sale.

[Anyone interested should contact Wes by email, with their

postal address, and he will pass their details on to

Brian.]

WW: So how would you describe your system within the

rest of the Duet systems?

BH: In the same way as the Maccann is related to the

English system, the Jeffries is related to the Anglo system. The

Crane is a rethink, and mine is a discovery rather than an

invention. That's the way I see it.

Its one of these things that I can't say I invented. I was

into trying to invent something on the concertina, to find the

best system. When I hit it I realised it was not so much an

invention as a discovery. This symmetricalness of it is something

that always existed but nobody had actually been there. There are

old Bandoneon systems that start to do something similar, but in

my opinion they got things wrong, they got things upside down or

backwards, and I worked out exactly the spacings and the angle of

the rows, which is critical, especially if you want to play

complex music.

WW: You said that you worked out the button spacing

for your system. If we compare hands, yours are not large, and

mine are small. But I find an English cramped to try to

play.

BH: On a lot of concertinas, the columns are too close.

The spacing on mine is wider along the rows (16mm), but slightly

closer than the spacings on an English or a Maccann between the

rows (9mm), which of course you can do with staggered rows, but

you can't with vertical columns, because when they are close

together the wood between the two will fall apart. With

staggering you've got a diagonal rather than a vertical.

The spacing on my original Crabb followed very closely the

spacing on a Jeffries Duet. The spacing that I later worked out

was because of the way my hands fell onto the notes. Because the

Crabb was an aluminium button concertina, you end up with grey

marks on each finger after playing for a time as aluminium is

continually disintegrating and going into an oxide. On my little

finger, on the tip, it was set back a bit and I realised that,

with the way I was doing it, it didn't need to be curved back,

and you were better to have a diagonal going away from the thumb,

rather than like a Jeffries Duet which go up a bit and come back

again. Its right if you're working around the rows, but its not

if you're working across the rows.

Its these little bits that are important. For instance, with

Steve Dickinson, I worked out the best way of doing it, and we

came to the conclusion that it would be better to have straight

rows rather than curved. I had them curving down towards the

thumbs, but it was easier to get the mechanical action between

the notes if they were identically spaced. With curves, they tend

to get closer to each other with varying spaces. If you use a lot

of common centered curves you tend to end up with wider spacing

at the top end, or things at different angles if you use the same

curve. If you just use straight lines you don't get that problem.

I discovered techniques of playing - because of the way the

system is laid out - that with a single finger you can play any

4th or any 5th throughout the whole range of the instrument. If

you are playing any complex piece of music, the likelihood of

4ths and 5ths occurring is quite high.

For one Hayden system made by Robin Scard of Dipper

Concertinas, I managed to persuade him to use bigger buttons, so

that has 6mm buttons. I did try to persuade him to go a bit

bigger, but that was a high as he was prepared to go. Colin had

made quarter inch (6.5 mm) buttons for anglos, but did not

recommend that on a Duet with so many buttons. It has worked out

extremely well, even when you are playing only three parts. With

four or even five parts, then you have to have it, and because of

the fourths and fifths, that tips the balance between being able

to play four parts and five parts. I haven't attempted any music

for 6 parts as yet.

WW: I hadn't realised how complex it had been for

you.

BH: Well, its been on-going. The Dipper concertina has

a very nicely curved hand rest, but I still feel its lower than

it should be.

WW: Have you seen the hand rest articles by Göran

Rahm?

BH: Yes, he's written to me a couple of times now, I'm

in the middle of replying to him at the moment. But everybody

writes to me with a few questions in a few sentences, but each

requires a huge answer, say 5 or more pages, with diagrams, and

so on. He's working on this higher handle, and I've recently met

someone else who's working on higher hand rests with thumbs going

through the rests for English and also someone else working on

hand rests for Maccanns. I'm also working on something at the

moment with hand rests, but until I've got something working, I

don't want to say anymore. But its an ongoing thing.

WW: You are never going to reach an end, are

you?

BH: No! The Horniman wrote to me recently about

on-going things with concertinas, again it took a lot of

answering. They were also asking for suggestions on display, and

I wanted to see working models. For instance the Jeffries riveted

action is the simplest to make, just a piece of rod with a

flattened section, then there's the flat action, where you need

to cut out the shape of the lever and round the ends that go into

the pad and the button. With the Wheatstone crank action you need

a lot of specialised tools. I was talking to some one recently

who didn't know what these all meant, although he'd been playing

for years, so people need to be able to see these things.

WW: I'm not sure I know what you mean by a crank

action.

BH: Well, the lever pivots on a hook, and the whole

thing is held in place by the pressure of the spring. The

Lachenal crank action does suffer from wear, for instance,

because instead of a hook it has a plate with a hole it it. In

the Wheatstone crank action, the hook is round and so the two

parts bed into each other, and wear together, whereas a riveted

action will need tightening up eventually.

So I think the Horniman should show you they way things work

inside. A long time ago, before instruments in the Horniman were

restored as they are now, they were falling apart in their cases.

There was this mellophone, a type of free reed instrument with a

guitar fretboard which is actually buttons and, with a

complicated mechanism of wires and pulleys to open the pallets to

play the reeds, and with a pump thing in the bottom you blew the

reeds. This was a sort of free reed instrument for someone who

only knew how to play the guitar. It was a ridiculous action, but

perfectly sensible for the time when no one knew how to arrange a

keyboard on a concertina type free reed instrument. Because it

was falling apart you could see all the details of the action,

but now its been beautifully repaired you think "What on earth is

this instrument and how does it work?". When it was all falling

apart you could see all that!

They do have the most important collection of an instrument

that is English, and not imported from abroad, the "Elgin

Marbles" of the concertina world, and they ought to give it

prominence in the centre of the museum. Get rid of the Walrus

perhaps? I think they should concentrate on musical instruments

as they do that quite well. They really have no equal, although

there are a few smaller excellent specialist instrument

collections, like the Bagpipe Museum in Newcastle for

instance.

Other Duet Systems

WW: What do you think of the old Duet

systems?

BH: The Maccann system is like the English system

folded so the upper notes of the two sides are on one side, and

the lower notes of the two sides are on the other. To play a

scale on the English, you go from side to side, but with the

Maccann system this becomes alternate fingers on the hand. The

Maccann system puts the two central rows of both sides of the

English into the centre of the keyboard, and the sharps and flats

into outer columns, so it requires six columns of buttons. The

Crane system fits the buttons into the minimum amount of width,

so it uses five columns of buttons, three inner for the natural

notes, and two outer for the sharps and flats.

WW : I've always thought the Crane system looked

more difficult to learn because the pattern for a scale doesn't

repeat. The C note, for instance, is on a different column in

each octave.

BH: Well, the Maccann does jump around a bit too,

outside of the centre of the keyboard, and there are variations

depending on the number of buttons on the instrument. But with

the Crane you can produce lots of chords with three simple shapes

of the middle three fingers. If you move these shapes backwards

and forwards from the handrests you can get the main chords, with

a change from major to minor, and so forth, being made by moving

an outer finger to an outer column.

WW: What about the Jeffries system?

BH: The Jeffries system is designed for anglo players

to learn, and is designed to be easily playable in a few keys

like the anglo. It has four curved rows of buttons.To play the

left hand C - E - G you use the same position as the anglo on the

third row from the handrest, but the buttons play the same note

in both directions. To get the notes you would have on the

outward direction of the anglo, you move back to the next row of

buttons. The row of buttons nearest the handrest allow you to

start the scale around an octave lower on the left hand, and the

front row contains the sharps and flats. Because of the layout,

there is a spare button position in the middle two rows, which is

used for B flat. On the right hand the second and third rows from

the hand rest play the same notes an octave higher, but the row

of buttons nearest the handrest extend the scale higher.

WW: When do you think the Jeffries system was

invented? I've only ever seen one that was C.Jeffries, Praed

Street. All the others seem to be Jeffries Brothers, so

1920s.

BH: The logical date for the Jeffries system would be

1900 or before. Maccann's patent was in 1884, Crane 1896, so I

think Jeffries would have tried to do something to meet the

fashion for Duets of that period.

WW: You've looked at all the old systems. How may

are there?

BH: Huge numbers. [Showing full manila folder]

These are all Wheatstones patents. and I've got another file the

same size of other patents. Inventing ways of arranging the

buttons on concertinas seems to have been a common pastime for

Victorian and Edwardian gentlemen!

WW: There are the obvious three, and I've seen a

Linton as well...

BH: The Linton is not really a duet system, its a

variation on an English type system. Its a split octave system

with alternate notes of the scale on each side, so its got six

columns on each side and the columns go up in octaves. It does

make things a lot more simple if you're trying to play harmonies

in several octaves at the same time.

There's the Linton system, Jeffries system, Crane system,

Maccann system, my system, the Piano system and the Rust system.

Quite a few! I've also seen one and a half instruments of an

early Wheatstone chromatic. There are quite a number of

variations on the Maccann system. There's a Chidley system that

repeats all the octaves identically. In fact there's a Chidley

system shown as a Maccann in the New Oxford Companion To Music

entry by Julian Pilling.

WW: I've seen a Piano type system in JEDcertinas

made by Lachenal in the 1920s or 30s, but what is the Rust

system?

BH: The Rust system, patented in 1862, is a variation

of the Piano system with a few extra notes on a third row. It

often appears on cheap, German-type quality instruments, although

I have seen a few instruments of a better quality. Piano system

instruments have been made from very early times. Crabbs used to

have a large Wheatstone Piano system instrument dating from about

1912 in their collection. Instead of the two rows of the

Jedcertina, this had many rows to give a much larger range, and

overlap between the hands.

Thats all I've seen. But there are two others that I know of

that are out there somewhere.

One is a system that appeared on the Antiques Roadshow [A

UK TV Programme], and I could see that it wasn't any of the

systems that I knew. It was a quality instrument, made by

Wheatstones, but it wasn't any of the standard systems.

[In 1999 a unique twelve-sided Wheatstone duet from 1938

embodying a duet system from the Wm. Wheatstone patent of 1861

but otherwise unknown was acquired for the Horniman Museum.

Full details are available on the web.]

There was also the 'Victory' system that Crabbs made one of,

just after the war. He sold it! Harry Crabb said he'd done one

and later I asked Neville about it and he didn't have any details

of how it was arranged. [Geoff Crabb has since said that

the system was named after the auto that Harry was driving, a

Vauxhall Victor.] He knew that his father had made this

one, but didn't know who he'd sold it to. He said he'd look it up

it the book sometime, but he died the year after and so I never

did get round to that one, and I think the book got lost

unfortunately. I saw that book, and that book would have told you

all the Crabb numbers. It had a complete list of the date it was

made, what type of concertina it was, how many buttons it had,

who it was sold to, and how much they paid. It was a hand written

book.

Harry Crabb had this idea running around in his mind that he

thought was an improvement on the Crane system. He played the

Crane system and he tried this one out and I think he showed it

to some one, and they liked it. I talked to Harry Crabb earlier

about getting all the details - this was before I was really

seriously into other than my own system of duets - and he

described it and and said he felt it improved on the Crane

system. Somebody had bought it, and been ever so pleased with it,

and then it just disappeared.

It must be out there somewhere unless its got burnt or thrown

away, and they don't usually get burnt or thrown away. It will be

some sort of variation on a Crane. Crabbs did do slight

variations on a Crane by putting very low notes on a sixth row,

only a few extra notes, but they did do variations.

WW: Did Crabb take over the Crane patent?

BH: The Crane patent was originally by a man called

Butterworth in 1896. I think Lachenal actually took the Maccann

patent for some reason but Lachenal started making Cranes as

well. How it became the Crane and Triumph system I honestly don't

know. But they do say some sort of connection with the Liverpool

firm of musical instrument dealers, Crane. You often see pianos

with Crane on them and I've seen many harmoniums with Crane on,

neither of which were made by Crane because they were retailers

rather than manufacturers. I think they still exist. They were a

very big musical instrument firm, the Liverpool equivalent of

Boosey and Hawkes.

They certainly would have dealt with people like the Salvation

army because I've seen 'Crane' on harmoniums which have come from

Salvation Army sources. The Salvation Army took up the Crane

because they were nice and easy to play a hymn tune with a few

accompanying chords on, but called it the Triumph system

I don't think Crabb took on the Butterworth (i.e. Crane)

patent, they just made them.

WW: I've got the Salvation Army Crane tutor.

BH: And it doesn't mention the word Crane once, but

mentions Triumph numerous times.

Those are the only systems that I know of that exist as actual

instruments, or are said to exist. There are numerous variations

on the Maccann. There's a Australian version called the Cheeseman

system that Richard Evans mentioned a few times in his Australian

Concertina Magazine, but I've never seen the button positions

written down as such.

WW: You wrote quite a lot for that magazine, didn't

you?

BH: Richard Evans once wrote me a letter asking me half

a dozen or so questions, all of which required about five page

answers to. I wrote him a very long letter, all half spaced, and

it cost quite a lot to post, as postage to Australia was quite

expensive at that time. Later on these answers were turned into

articles and appeared in three or four of these Concertina

Magazines. Unfortunately some of my research at that time was not

as complete as it now is, so there are errors and omissions in

that. For instance, I didn't know that the Crane system was

invented by this man called Butterworth in 1896 at the time I

wrote those answers.

WW: Now you've done all this research, have you any

plans for it? A book maybe?

BH: You're joking! Most of this information is general

knowledge, I'm sure its available on the internet.

WW: I don't think so. For instance, there's no

diagram of a Jeffries system that I know of anywhere.

BH: I'll find you one. The Jeffries system diagram,

incidentally, is described in my patent application. Patents

require you to write a background section, and anything that is

not in a previous patent or published work has to be described in

full. There are so few Jeffries systems now, because they've been

converted to Anglos.

WW: Do you know of any Jeffries players?

BH: I've come across two or three, there's one who

plays mainly hymns beautifully, there's another who plays jazz

extremely well, and another who emigrated to Australia.

Learning and Playing

WW: I've heard you are writing a Tutor.

BH: I've got a whole load of stuff in a tune book, for

my workshops. They were first written for Witney. I did this

beginners course and I didn't know what was going to come up so I

wrote out all the Duet systems, a basic keyboard diagram and

chord diagrams for each, and it was Cranes, Maccanns and Haydens.

No Jeffries turned up.

WW: All your workshop notes are type set, but I

thought you didn't have a computer?

BH: I've got a word processor - an ancient Amstrad PCW.

I've got a little program that allows you to alter some of the

letters into shapes, and by altering only 16 letters I can write

music. I was very proud of it when I first did it, about fifteen

years ago, as the music I'd seen from computers was very jagged

compared to that.

The musical pieces start as one note on each side, then two on

each side, working up to 6 notes on each side. But the thing I've

learnt over the years is to use use both sides at the same time.

Most important! People make the mistake of learning just the

right hand side, and getting quite good with it, and then trying

the left hand side. When they try to follow at the same sort of

speed, they find they can't. Because they don't know where things

are, and they don't know how to read the music on the left hand

side, they then make do with just a few chords.

So that's the way I teach; I think its so important to have

both hands together. When I learn a piece nowadays I learn it bar

by bar, all of the notes together. I never go on to bar two until

I've got all the notes of bar one. I may initially learn the

right for two or three notes, but then you immediately must put

in the left hand side. Sometimes, to get the best possible

fingering for a piece, you need to play a 'right hand' note on

the left hand, and vice versa, if you have that note on both

sides of the instrument, and that is best worked out and learnt

when you first learn a piece, rather than have to relearn a new

fingering later.

'Both hands' is THE absolute essential for the Duet

concertina, otherwise you get to a stage where you are uneven or

you can only play the right hand side. If you always do them

altogether, then that's the best way. Its not the way I started.

As I said, I started with an accordion thing with my own system

on the right hand and a Stradella bass on the left.

WW:And do you have plans to publish this

tutor?

BH: Eventually. I've got whole load of material, but

thats got to be turned into proper things. I've got lots of notes

but, for instance when I teach how to play a certain kind of

scale in a lesson, I can just do it there and then, but that has

to be written down with music and diagrams as well, and that

takes a bit longer.

I've got about a dozen different ways of doing re-iterated

notes, but that has to be explained with diagrams. Its very easy

if you've got your fingers there to show how to do it, but to

write it all down takes time. You can show things so easily.

WW: The old Duet players would talk about 'balance'

as a technique, between the bass and treble. What's that all

about?

BH: You play the treble notes more or less joined up

together, with tiny little spaces between them, and you play the

bass notes about half of what the note indicates on the

music.

Thats what I would always do for any sort of folk thing. You'd

be playing a tune, where tune is played continuously but with

tiny little gaps, and the bass is played like 'Um, rest, Pah,

rest. Um, rest, Pah, rest.' ..and keeping it very light.

The other thing is, there was a piece of music that I decided

to play, and one bit had some very high up notes in it, from

Handel's Firework music. I thought the very high notes had almost

disappeared, but the thing in total sounded alright. I could hear

the high notes coming through, so I thought "What do they sound

like on the original?". I've got a recording of the same with a

complete orchestra, I listened to it, and I couldn't hear these

high notes at all on my tape recorder. So I got a better set of

earphones for my Walkman, and still couldn't hear them. I tried

the same thing on a hi-fi tape recorder with speakers, and on

that one I could just about hear these high notes. I've realised

that balance, because of the way he'd composed the music, that it

was like a descant, the very high notes were a descant rather

than part of a melody.

WW: So more to give a feel than actually be up

front?

BH: Like adding harmonics to the thing. The bass was

strongly coming through both on what I was playing and what I was

hearing on the recording, because that was where the theme was -

there is no top line tune in much of Handel's music, its total

harmony! It is a good idea to study music EXACTLY AS COMPOSED by

first rank composers like Handel. The high notes - the fact that

they are softer- happens on an orchestra as well. If it happens

on an orchestra, why complain about it on the concertina.

WW: It wasn't a complaint I think, just an

observation..

BH: I know exactly what you mean, and if you are very

heavy on the bass it can just drown it out. The third thing is

that I play a lot with groups that have huge numbers of English

Concertina players. I walked into the room once and sat down -

there was a unison tune only sounding - and took my concertina

out and started playing, and of course with the bass, although I

was playing maybe even a heavy bass, added to all these other

instruments, it was balancing up what they were playing.

So I do a lot of that when I play for dances. There may be a

dozen English Concertina players who haven't got any idea that

anything exists except the single written melody line, and I'll

sit and I'll play a harmony on both sides, [laughing] as

loudly as I can, in order to try to balance it up. So there are

different aspects of balance.

Its just when you are playing by yourself maybe, you've got to

balance it up. As I say, keep it short and light on the bass.

Keyboard Diagrams

(Click on any diagram to see a larger illustration.)