Note for the web edition

The four instalments that make up ‘Faking It’ were originally published by the

International Concertina Association during 2004-5. Intended for inclusion in the

newsletter, Concertina World, they in fact appeared as an appendix to the ‘Music

Supplement’ which allowed an A4 format.

In preparing the pages for this web-based version I have made some minor changes,

based on observations received in the interim, (Doug Watt was particularly helpful), but I

have maintained the episodic nature of the 4 parts in order to emphasise the necessity to

stop, reread, absorb and practise.

I have tried to achieve clarity and simplicity and keep musical theory to the essential

minimum. Nothing can replace the necessity of practise and the familiarity which can be

achieved by it.

There has been a lot of recent interest in what is being described as ‘The English Way’ of

playing the Anglo. This is becoming a description for the technique of playing the tune

on the right hand while using the left hand to provide chords and rhythm. There is

evidence in early written tutors that this approach is as old as the Anglo itself. It’s

independent ‘discovery’ by a large number of players in recent decades suggests that it an

obvious way of approaching the instrument. The practise of ‘Faking’, based on the

tune/chord pattern published in Fake Books, reflects this approach. I believe this is a

completely legitimate way to play the Anglo which, once understood and practised, leads

to more adventurous ways of developing left hand techniques.

For the web version I have added a dozen examples

of what I describe in the text. I have chosen twelve tunes that are common in sessions and

include most of the dance rhythms, six tunes in C and six in G as the most common Anglo keys.

Each tune is represented by the music (printed without chords), and also by a sound file of

Anglo concertina played as you might hear it at a casual session.

I am very happy to respond to any individual queries which this piece may suggest.

I repeat that there is no substitute for diligent practise.

Good luck.

Part 1

A recent discussion on ‘Fake Books’ in the online newsgroup created

the request that someone explain how to use them. It’s a fascinating feature

of music that what is a commonplace to one is a mystery to another. I first

discovered the approach of ‘Fake Books’, or ‘Busker’s Books’ as I usually call

them, when dealing with sheet music in the 60s for piano or guitar. The piano

score could be ignored and a competent version could be built up around the

top line of the score, i.e. the tune, and the chord name or sometimes ‘guitar

shape’ which was placed above or below. In ‘Fake Books’ the piano score is

left out and you are left with just the tune and the chord. So fundamental is

this to my musical playing that this is effectively all I do. It’s how I play and

think, whether the tune is written or simply in my head by ear.

It seemed to me that I was therefore well placed to reply to the

online request for an explanation of how it’s done, not least because ‘What to

Do with the Left Hand’, ‘The Three Chord Trick’, etc. are frequent themes

of mine when giving Anglo Workshops and the subjects are inextricably

linked.

First of all some caveats:

-

I can only write about the Anglo; it’s all I know. I am grateful to

Kurt Braun, a Crane system player in Baton Rouge, who is also a Fake book

busker, for contributing a fourth part for Duet players.

-

I am going to assume a starting point of zero, so some readers

might find some of this very, very basic. If so skip those bits!

-

I will inevitably have to employ some musical theory. I’ll assume

nothing here as well so the same advice applies to those readers who are

musically literate.

-

I don’t really start answering the question in this first episode!

Basics first!

Next some very fundamental theory:

The names of the notes

Convention names the notes by the first eight letters of the alphabet (A -

G) and whichever note is the starting point for the eight note scale names

the scale; so, the scale of C starts on C and is said to be ‘in the key of C’, the

scale of F starts on F and is said to be ‘in the key of F’, and so on. Anglo

concertinas have the two home rows tuned to keys that are a ‘fifth’ apart.

This means that the inside row starts on the same note as the fifth note on

the middle row (or on the upper row when there are only two rows).

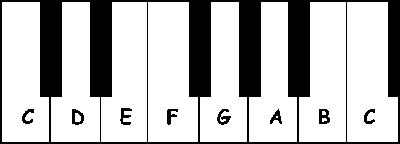

The major scale

This is a standard series of notes based on tones and semitones, the latter

being one half of the former. The intervals of the scale are tone, tone,

semitone, tone, tone, tone, semitone. This makes visual sense when shown on

a piano keyboard. The Key of C, which has no sharps or flats, runs up the

white keys.

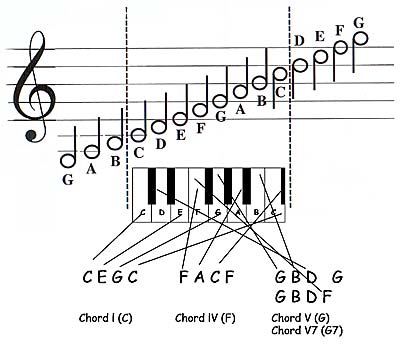

Make a real effort to understand this graphic. It’ll come back later.

The interval between the C and D is a tone with the black note between

being the semitone. The desired semitone between the 3rd and 4th note and

the 7th and 8th note is automatically in place.

If the scale is started on a different note then some of the black notes (the

sharps and flats) must be brought into use to maintain the relationship of

tones and semitones. If the fifth note up the scale (G on the example above)

becomes the starting point (the key note) then the F must be raised to an

F# to maintain the correct tone/semitone relationship on the last three

notes. Every time you go up a fifth you need an extra sharp. The function of

‘flats’ has the same purpose.

I’ll leave it there for now! I think the logic of it is clear from what I have

written, but you might need to reread it and try out some examples.

Now let’s turn to our Anglo.

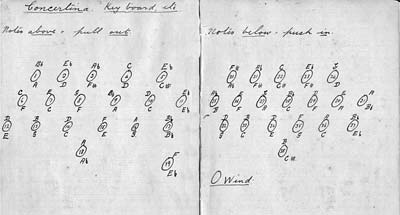

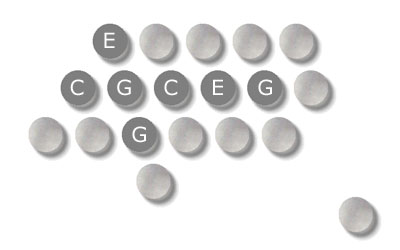

First of all, know what notes you have on your instrument! This is not as daft

as it sounds. Most of us Anglo players know what we have on the home rows

but are often very hazy on the top row. I usually know(!), but have to think

for a second, especially when there are variations between instruments. If

you have never done so , map out your instrument.

Here’s the front page of one of Jeffries’ own instruction booklets,

written for an F/C 38 key and it shows one way of doing it.

(This booklet came with a concertina which is actually tuned to F/C high

pitch, but it seems to have always belonged to that instrument. The entire

booklet is reproduced elsewhere on this site.)

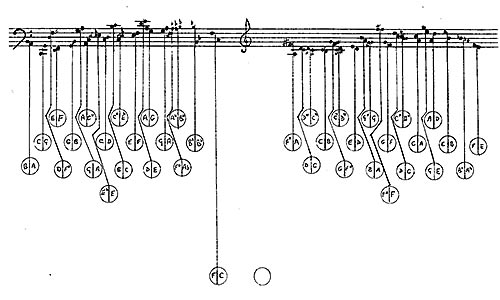

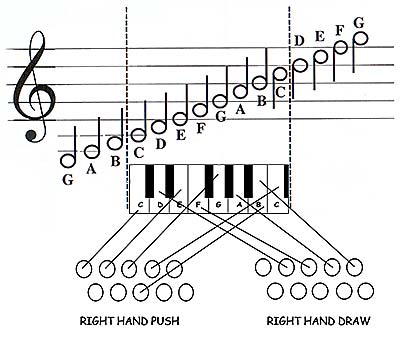

Here’s another way that links it to the musical stave for those who can use

that; this for my C/G Crabb:

which is probably as much detail as anybody could ever need! (There's a

blank diagram like this at the end, to print and

fill in for your concertina.)

Of course to map out at all requires some knowledge of music and those who

play entirely by ear won’t have a starting point. So to go back to the very

beginning, it’s a fair bet that the basic 20 buttons at the heart of the Anglo

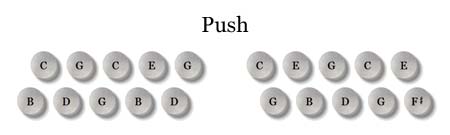

are tuned like this, (assuming a C/G):

(The reversal of the F# and F on the rightmost button of the lower row is a common variant.)

If your instrument is not C/G, the intervals will be the same. i.e. if you have

a G/D every note will be a fifth (five notes) higher (though an octave lower

in pitch, but don’t worry about that.). For additional buttons, first find the

ones that give an already identified note in the other direction (there are

probably two in each direction). After that you will need to use your ear if it

is up to it or call on a friend with a piano or other fixed pitch instrument.

What this is all leading up to is your ability to form chords on the left hand.

You know what all your buttons do? Yes? Then we can look at chords.

Major chords

Full major chords are formed from the first, third, fifth and eighth note of

the scale (the shorthand is 1 3 5 8) so in the Key of C, as depicted in the

piano keyboard earlier, the notes will be C E G C.

Find these notes on your left hand PUSH direction. They will almost

certainly be:

Now this is fine for those of you with seven fingers on the left hand, but

what it clearly indicates is that we are sometimes faced with choices. More

of that next episode!

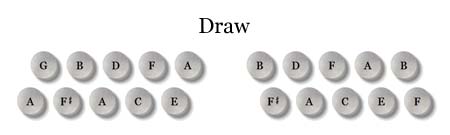

To start with, work out finger patterns like this for the PUSH and DRAW

for four major chords:

-

the two for your home keys,

-

the key that is one sharp up from your inside row,

- the key that is one flat down from your middle row.

On a C/G

instrument this means the home keys of C and G, the key one sharp up from

G which is D, and the key one flat down from C which is F. On a G/D the four

chords are G D A C. (Remember that what I am calling ‘the key that is one

sharp up’ will start on the fifth note of the scale. The ‘key that is ‘one flat

down’ will start on the fourth note to maintain the relationship.)

Use the blank sheet at the end for this. Simply ignore or cross out buttons

you don’t have, and add any you need!

In the next part I’ll endeavour to explain how to use this knowledge of

chords to get you started on ‘Fake Books’. In the third part I’ll explain

bluffing the 3 chord trick.

Part 2

Introductory Note

In this part we’ll finally get to look at the ‘Fake Book’ approach of

tune/chord, but first a couple of points from the last episode!

I explained that the shape of scales is a constant with the name of the key

coming from the first note of the scale. Therefore to play a tune in G is

exactly the same as playing it in C except that the key is a fifth higher. On

the assumption that this is understood, I intend to proceed on the basis of a

concertina pitched in C/G, which is, I believe, the most common. Those with

G/D or other pitches will need to make the mental key shift. (mutatis

mutandis as we used to say!) The four chords that I urged you to discover at

the end of part 1 shall therefore be known as C G D and F.

Let’s begin with looking at those chords and the problems you may have

encountered.

Problem 1. Some of the chords are very thin and lack certain notes.

Players with less than 30 keys will find this frequently as we proceed.

Players without a left hand thumb button will have found the draw C very

thin and the push F lacking the key note. (If your left thumb button is a

drone C rather than the much more useful C/F consider getting it changed! I

see no point in duplicating the C which already exists on the push in the

middle of the second row.) The push D is thin on the 30 key as the most

common layout lacks a push F#.

There is no solution to this problem except not to see it as a problem. Every

instrument has its individual limitations, but trumpet players don’t dissolve in

despair because they can only play one note at a time, nor guitarists lament

because they only have 6 strings. My favourite examples in this context are

musicians like Oscar Woods on one-row melodeon and Jim Small on

mouthorgan. These are very ‘limited’ instruments but Oscar and Jim could

hold you spellbound. Accept what you can—and can’t—do and work within it.

Don’t give up!

Problem 2. There are more notes available than fingers to play them.

In this case you have to select. If the key note is available as the lowest note,

use it. The use of the ‘third’ or ‘fifth’ opens up issues of harmonic theory which I

don’t understand and is not relevant to the concept of ‘faking it’. You can pursue

this area if you wish once you’ve understood the basics.

Problem 3. For mechanistic reasons (leaks, small bellows, set of the reeds)

the air runs out very quickly.

You need not play all available notes all the time and this is something I’ll

return to in a minute.

Before proceeding, recheck that you know which buttons are available to you

on the Pull and Draw of the four chords. (i.e. Check your homework!)

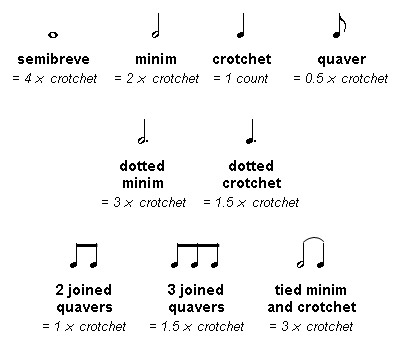

Written Music

Like it or not, Fake Books will give the tune in conventional notation. I know

various alternatives have been devised for Anglo concertina; you won’t find

these in publications. It is therefore essential that you can read the notes

on the stave at least in the treble clef and know the value (length) of the

notes. This is not hard and should only take a few moments of serious

application. You only need to know the very basics and your ‘mapping out’,

which is where I started in Part 1, will have got you started.

I hope the following diagram explains more than words.

I genuinely believe that there is enough here, together with the mapping out

process of Part 1, to understand the notation of the treble stave and relate

it to the Anglo.

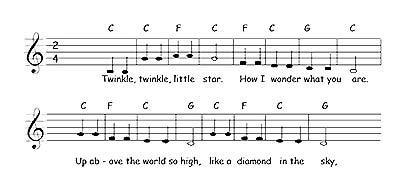

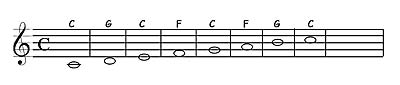

Here’s a simple rhyme as it could appear in a Fake Book:

Repeat the first line.

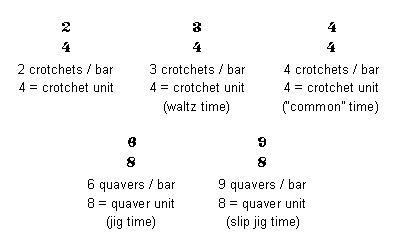

Let’s look at the rhythm first. The numbers at the beginning form the ‘time

signature’. Here are some examples:

The lower number in our music (4) tells us that the basic unit is the crotchet (which

is the most usual unit in time signatures) and the upper number (2) indicates

that there are two of them in each bar (i.e. between the upright divisions).

The most common time signature is four crotchets per bar, thus known as ‘common time’ and often

represented by a letter ‘C’ in place of the two numbers.

Waltz time is three crotchets per bar.

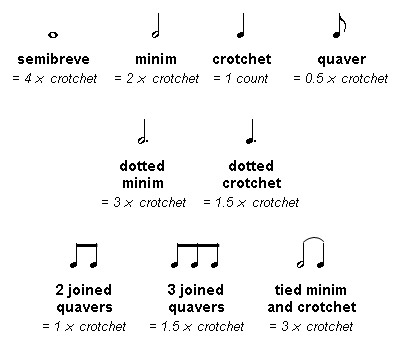

The ‘hollow’ notes in our music (e.g. on ‘star’, and ‘high’) are called minims,

with a time value twice as long as crotchets. The other common notes, not in this tune,

look like crotchets with tails and are called quavers, with a time value half as long as crotchets

(i.e. twice as fast).

Quavers can have their tails joined together visually, with a time value which is the sum of the

joined up quavers but the individual notes are played separately.

If the quaver is the basic unit of the rhythm this gives a lower number of 8 (4 x 2) for the

time, so six quavers per bar is typical of jigs, and nine quavers per bar typical of slip jigs.

It is unusual, but not impossible, for the minim to be the basic unit, giving 2 as the lower number.

You should also be prepared to meet ‘dotted notes’, where the dot after the

note indicates that the note is half as long again, and ‘tied notes’, joined by

an upper arc, which indicates that the tied notes are added together and not

played separately,

Always stress the first beat of a bar.

I think that concludes the musical theory for part 2!

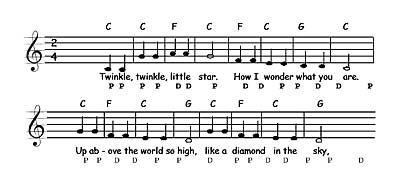

Here’s the tune again with the addition of P (push) and D (draw) indicating

what will almost certainly be your bellows direction as you play the tune.

All that remains to do is unite the tune and the chords! In the first bar and

second bar you will play your push C chord, in the third bar your draw F

chord and so on.

And that’s all there is to it - at least in theory. In fact it’s only the starting

point, but it answers the original question of how to use a Fake Book.

Let’s face it, stopping now would be pretty silly, so let’s go a bit further. If

this is your first experience of working with chords on your left hand you

are probably still fairly bewildered. Just how do you use them?

You can play the chords crisply in identical rhythm to the tune. This leads in

a Kimber direction and will please dancers who will want your left hand to

provide their steady foundation. A singer, however, might not want an

accompaniment that was such a tight straitjacket.

You can break the chords up playing the bass note on the first beat of the

bar and then bringing in some other notes on the second beat (boom - chink ,

boom -chink). This is particularly good for waltzes (BOOM - chink - chink,

BOOM - chink - chink).

You can select individual notes from within the chord to make bass runs,

counter-melodies. And, of course, you can do all of them together! You have

months of experimenting ahead. The sky (and your bellows) is the limit!

One word of advice. The great quality of the Anglo is the crispness which

derives, in part, from the double action. This is greatly diminished if you

allow the change in bellows direction to change the chord for you which is

very tempting on the middle row. Practise changing bellows direction in the

split second between beats and with no buttons down. Once you can do this

you can decide when and if you want to do it. I often keep my little finger

down to provide a smooth bass presence below the rest of the chords which

I keep crisp.

More Chords

You will, of course, need more than the 4 chords we’ve used so far. Based on

the explanation of chord structure in Part 1 you can work out any major

chord you want. Now is the time to print up some blank chord charts

and start working out and filling in a few more chords. Some chords will be very thin,

but will usually give you enough to suggest a passing chord.

(Some of these chords will sound out of tune if you have one of the very few

concertinas still in existence that originated in uneven temperament and have never

been retuned. This tuning recognises the difference between, say, C# and D flat.

The quality of their tone is incomparable but a lot more care is needed in choosing

the correct notes for a chord and there are very few options. I had a beautiful

uneven G/D and parted from it simply because I couldn’t find the chords in their

’usual’ places. I’m delighted to say I eventually bought it back—never to be retuned

in my lifetime! If you have one—treasure it.)

The chords will

not be full enough to allow you to play with big chords in, say, the key of

Eflat. Fred Kilroy, probably the greatest exponent of playing outside the

home keys, employed runs and ‘broken chords’ (i.e. one note at a time) when

in the outer keys. Irish players who get around the keys all over the place

seldom play more than the tune.

Other chords

For Minor chords, depicted with ‘m’ or ‘min’ after the note, (e.g. Cm or Cmin)’

the third note of the scale is lowered by one semitone, so the 1 3 5 8 for Cm

is C Eflat G C.

Seventh chords, depicted with a 7, (e.g. G7) include the 7th note of the

scale, so G7 is the G chord with the addition of the note of F. This seventh

is very common and NOT to be confused with a major seventh.

Then there are 6ths, flattened 5ths, diminisheds, augmenteds, sustained

4ths and heaven knows what else and if you find yourself encountering these

you’ll be so far advanced that you’ll understand them when you meet them!

You’ll probably also have changed to the piano! Seriously, don’t abandon a

piece simply because you haven’t the buttons for such and such a chord. This

is ‘Faking it’ - the art of fudging and getting away with it. Every musician who

doesn’t work to a definitive score does it a lot of the time, but, of course,

that’s a secret which you are duty bound to keep.

One final word for Part 2. Don’t expect to be able to understand and do all

this in a matter of minutes. Even if you practise hard you may still not be

there by the time Part 3 hits the printer. Don’t worry. There are not many

who can learn an instrument quickly and after 30+ years I’m still working out

new chords and new ideas.

In Part 3 I’ll look at how to fake it when all you have is the tune in your head!

Part 3

(in which there is also some consideration

of chords in traditional music)

In the first two parts I’ve tried to explain how a Fake Book works, how to

know what notes make what chords, and how to map these chords on the

Anglo’s left hand. I’ve also suggested different approaches to using and

selecting notes from within the chords.

Part 3 looks at the ultimate practice of ‘faking’: how to create a full

rendition of a tune or song when all you have is the tune.

The starting point for this is the ‘Three Chord Trick’, known and relied upon

by buskers and bluffers the world over. By using this trick, three chords can

fill the place taken by the given chords in the Fake books.

The three chords in the trick - for any key - are the chords that start on

the key note, the fourth and the fifth, regularly depicted in Roman numerals

as I, IV, and V, which has the advantage of being non-specific in terms of key.

For the key of C major

I is C, IV is F, and V is G, but this chord is frequently V7,which gives G7 here.

If you do a rethink on lV and think of the F an octave lower you will realise

that all these chords are a fifth apart so C is a fifth higher than F and G is a

fifth higher than C. I mentioned earlier that each time a key note moves a

fifth higher another sharp is needed so these three chords are adjacent in

the cycle of key signatures. (Just another example, really, of the

mathematical symmetry that shapes musical structure.)

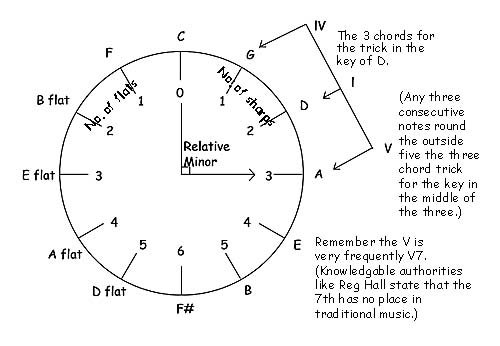

If you think of these key progressions as a circle you come up with this: The

Circle of Fifths.

The relative minor, to which I shall come in a moment, is a 90° turn

clockwise, so the relative minor of C is Am, the relative minor of G is Em, and

so on.

Don’t worry if this is not immediately clear. If you are starting out you only

need to know the three chords for your two home major keys.

I am now returning to a graphic with which you should be familiar from

Part 2, but this time I am placing below it the 1 3 5 8 notes of the three

chords in the trick for the key of C.

From this you can see that all the eight notes in the Scale of C occur within

the three chords and those that give their names to the three chords (C,F,

G) occur in two chords. This means that the chord that contains the note

being played can be accompanied by the chord that contains it.

Put in Fake book terms the scale could be expressed thus:

These hollow notes without an upright are called ‘semibreves’. They are twice as

long as a minim and therefore last as long as four crotchets. They take up a whole

bar in ‘Common Time’.

Practise playing this scale until you can do it in your sleep and your fingers start to

move into position instinctively when you know what note is coming up in the tune.

For the notes that occur in two chords you will have to rely on your ear, but there

are some generalisations that should help. The key note is most likely to require the

I chord rather than the IV. A tune is virtually bound to end on the key chord (I). The

fifth will tend to take the V at the end of a phrase, but I at other times. Be warned:

these are guidelines, not rules. Your ear must tell you.

Some people lack confidence in their ear, but … ears can be improved. If you

really work on the scale on the previous page you will soon start to hear and

distinguish the different chords. If you know a fellow musician ask him or her to

play the chords (on any instrument) while you try to identify them. It will come with

practice.

Other chords

If a chord from the three chord trick does not sound right the first place to look

for an alternative is the relative minor. Every key has one, so every major chord has

one. These are indicated on the Circle of Fifths. Try this first.

If the tune contains an ‘accidental’, i.e. a note that is not in the major scale, this

nearly always indicates the need for a chord outside the three of the trick. Look

for the nearest chord that contains the accidental. The most common accidental in

the key of C is F#. You only have to move one key around the Circle of Fifths to

encounter the chord of D which contains F#. This is the one to try first and will

usually be right. It invariably leads into the V chord and this is a chord progression

the sound of which you will come to recognise with practice.

Other common chord patterns

The pattern (in C) of C – Am – Dm – G7 – and back to C

is so common it has its own name,

‘The Blue Moon Sequence’, because it is the basic structure of that well-known song.

If you find that a relative minor sounds right, the ‘Blue Moon Sequence’ may well

lead you back home.

Another common pattern in Ragtime and often found in popular song involves going

immediately from the Key (tonic) chord to the VI (A major in the key of C) and then

round the circle to home, usually with 7th chords. E.g. C – A7 – D7 – G7 – C.

Minor keys

The trick can work for minor keys, but you need to be aware of more possibilities.

The key of A minor, for example, could use a lot of E7 and D. It could also use a lot

of G, the V chord in A minor’s relative major, C. This depends very much on the

nature of the tune.

Don’t worry if this is not crystal clear on first reading. If you persevere,

understand and practise you will be able to structure whole versions of tunes from

just the melody line.

Unless your ear is spectacularly good you will find some tunes are crying out for

other chords and you can’t find them. When this happens you need to go and find a

Fake Book. Some composers, like Gershwin, are virtually unbluffable. We all have

our own thresholds!

The ‘right’ chords

I can’t leave this topic without some thoughts on ‘right’ chords. I have already said

that your ear is your guide, but it is easy to be mislead. There has, in my opinion,

been a deliberate attempt by some music-publishers to impose unnecessarily

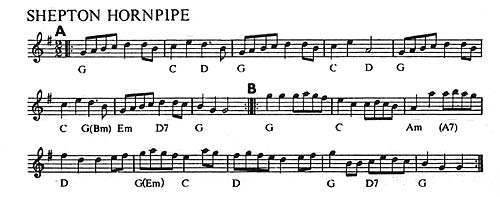

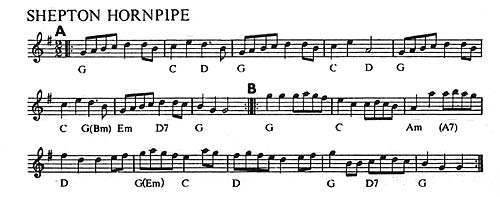

complex chord patterns onto traditional tunes. Here’s Jim Small’s ‘Shepton Mallet

Hornpipe’ as it appears in an EFDSS Country Dance Manual.

As far as I know Jim Small was the source for this cracking tune. Jim played

harmonica in a superbly rhythmic style. A harmonica player’s mouth covers about

three holes of the instrument and the tongue is used to block out the two holes

(invariably the two holes lower down) in order to play the tune. By moving the

tongue on and off these holes the accompanying rhythm is created. Choosing a

chord is impossible. There are the two holes available and that’s it! Jim could not

have played the chords printed. Have these have been added to make the tune

‘more interesting’ (!!) or as a sop to the omnipresent piano accordions with their 180

button basses?

I think these chords should be rejected as simply too contrived.

There are two statements that are held to be true by very highly respected

experts on Traditional British Music.

-

There are no sevenths in trad. music.

-

There are only 2 chords in traditional tunes. (I and V in major keys; I and the

V of its relative major in minor keys.)

I am not going to discuss this here, but it is a warning against piling on the chords

just for their own sake. With traditional tunes - keep it simple.

The one observation I would make is: I think that at the back of theories like this

is the awareness that a lot of traditional tunes are not constricted by the (post-

Hanoverian?) determination that everything is major or minor. I may well be wrong

in this, but as you get more familiar with certain ‘minor’ tunes, particularly slow airs,

you might try leaving the third out of the chord and thereby not defining the chord

as either major or minor. This is just a whole lot more to think about!

This concludes my attempt to explain Faking It on the Anglo. It may seem a bit

intense and involve a lot of practice, but I believe that all you need to know is here.

In the next issue of Concertina World Kurt Braun will take on the topic from the

point of view of a Duet player.

Good luck with your playing.

Roger Digby

June 2005

Part 4

The Duet Concertina

by Kurt Braun

Introduction

This part discusses ‘faking’ in the context of the duet concertina. The differences

between faking on a Duet and an Anglo have to do with the number of notes

available and the fact that the Duets play the same note on pull and draw while a

single stud or key on an Anglo changes pitch based on the direction of the bellows.

Consistent with the previous three parts of this article, the discussion is focused

on the left hand.

Faking here refers to improvising arrangements given a fake sheet. A fake sheet

is, as

Roger described earlier, the melody and chord symbols. There are two main

sources for such

sheets. The first is what are called fake books. A second source is popular sheet

music arranged for piano and guitar. What the concertina player can do is ignore

the piano score altogether and focus on the melody line and the chords intended

for the guitar. The piano score is ignored because it is out of range, overly complex

or otherwise impractical for the duet. The most common problem for the faker is

to find something musical to do with the left hand to support the melody being

played in the right hand.

Voicing

The keyboard of the duet though small, contains all chromatic notes. Roger's point

about

having to be satisfied with thin chords does not apply. With one hand an

experienced player can get fingers over just about any four notes in the left hand

which is frequently in a two (or more) octave range. If there are three Cs two Es

and two Gs available, the problem becomes which three or four of these notes are

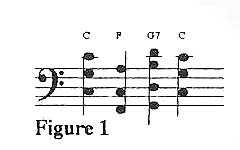

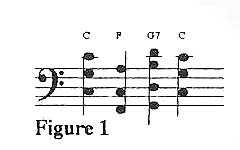

going to be used when a C chord is called for. The following figures show three of

many possibilities with the I, IV, V7, I progression in the key of C available on my

instrument.

Figure 1 uses open chords. These are rich and often preferred in arranging. When

voicing open chords it is common to consider the melody as well and much thought is

usually needed to get things to work out correctly. This requires more forethought

than generally consistent with faking when the point is to come up with patterns of

playing that reduce the players options or need to think. That is, the sort of

progressions depicted in Figure 1 require too much thought for faking. We need to

reduce the choices and make automatic the production of chords in the left hand.

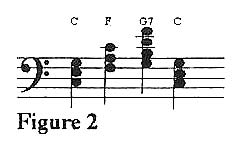

One way to do this is to play closed chords in root position as in Figure 2. This sort

of playing is found on the "one finger chord" setting of an inexpensive keyboard. It

is also similar to what you get from most accordions. It works, but it is pretty

basic and not very interesting. Worse, on the concertina it will often force low

closed chords, which sound heavy and not suitable for anything lighter than a dirge.

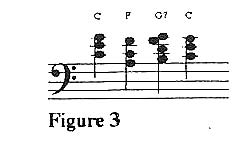

Another way is to play in one place and let the inversions go as a function of keeping

the chords high on the keyboard as in Figure 3. With some practice, this does not

require any more thought than playing chords in root position. It is also easier

because it requires less hand and finger movement. Finally, it is more interesting to

the ear.

With the closed root chords scheme all movement is the same from voice to voice.

Notice the first change, from C to F (up one fourth) in Figure 2. The C moves up a

fourth to the F. The E moves up a fourth to the A and the G moves up a fourth to

the C.

In Figure 3, things are different. The first progression is still from C to F. The C

and the E each move down a minor third while the G moves down one step to the F.

At the same time, the ear also picks up the fact that the progression is from C to F

or up a fourth. This is much more complicated and interesting for the ear, a great

benefit considering that it also made things easier for the fingers. These sorts of

interesting voicings are a natural byproduct of holding the chords on one place on

the keyboard.

Using this little bit of theory, we can make the following rules suitable for chord

production when faking on duets.

When faking, generally play left hand chords as high up the keyboard as possible

and play them in closed position. Playing chords high prevents them from being too

heavy. Closed means that no notes of the chord are skipped. Playing chords closed

also brings out the dissonance (jazzy quality) to the 7th and 6th (four note) chords.

Doubling notes adds unneeded complication, so play only the three notes of triads,

but play all four notes of 7th chords. In summary:

-

Play chords as high as possible on the left side

-

Play chords closed without regard to inversion

-

Do not double any notes

One may allow these rules to overtake all other voicing decisions and thereby

reduce the amount of thinking so one can concentrate on style and other musical

matters. This strategy, by ignoring inversions, also reduces the number of chords

your left hand needs to learn. Let's see how that works.

The 31 chord trick

Much has been made of the 3 chord trick. For moving past 3 chord songs there is

also what could be called the 31 chord trick. These 31 chords will cover any song

you will find a fake sheet for and in any key. For all practical purposes, the entire

universe of chords can be reduced to a mere 31 patterns on the left hand.

Again, forget that there are all these inversions (root on the bottom, third on the

bottom, etc.) because in faking on a concertina as described above, they are not a

consideration.

There are

12 Major chords (triads or three note chords)

and 12 Minor chords (triads)

and 12 Major chords with flat 7th added (V7 chords)

and 12 Minor chords with flat 7th added

and 12 Sixth chords

and 12 Augment chords

and 12 Diminished 7 chords

This gives a total of 84 chords. Inversions are ignored. The 12 sixth chords can be

subtracted because they are the same as the minor chords with a flat 7 added

chord. For example Cm7 ( C, Eb, G, Bb) equals Eb6 (Eb, G, Bb, C). After

subtraction there are 72 chords left.

Again, ignoring inversions, there are only thee Diminished 7 chords. C, Eb, Gb, A

are the notes for Cdim7, Ebdim7, Gbdim7, and Adim7 chords. The other two

diminished chords are C#, E, G, A# and D, F, G#, B. Diminished chords are lovable

because they are so simple and yet so many people think they are really

sophisticated and difficult. So instead of 12 Diminished chords there are only 3.

That is 9 we don’t have to learn. Now we are down to 63 chords.

Similarly, there are only four augmented chords (C,E,G# for C5+, E5+, Ab5+ or

G#5+; C#, F, A for C#5+ or Db5+, F5+, A5+ and so on for D, F#, A# and the set of

Eb, G and B. That is 8 we don’t have to learn. (63-8=55)

There are 55 chords left. The V7 chord is a major triad with a flat 7 added. So,

when you learn the V7 chords you only have to subtract the 7th to get all of the

triads. Another 12 chords gone and we are down to 43 chords.

What goes for the V7 chords also goes for the Minor triads with the added flat 7.

That is, drop the 7th and you have all the minor chords. That brings you down to 31

chords. If you learn 31 chords you will be able to play virtually any chord in all 12

keys. If you decide that you will never be playing in the key of Db or B, you can

drop a few more chords from your to learn list.

What about 9th, 11th and 13th chords? Play the corresponding 7th chord and move

on. That is what faking is all about.

So, by learning 31 chords you can fake the world into thinking that you know all

chords including 6th chords, diminished chords, augmented chords, the 9ths the

11ths and the 13th chords and that you can do this in any key.

One need not learn all 31 chords all at once. Most players will start out by playing

in just a few keys. This is so often the case that it goes a considerable way to

explaining the popularity of Anglos over Duets; that is, the capacity of a Duet to

play in any keys is not needed and is an unnecessary burden for many or most

concertina players who are going to play in just a few keys anyway. But for those

who take up the duet, the ability to play in a large variety of keys can come

gradually and players will find that if a new key is not too distant from keys already

known, only one or two new chords need be learned to be able to fake in the new

key.

Putting Chords to Use

Straightforward chord production as described here will do much for faking

arrangements on a duet. This is especially true for tunes where the harmony

marked on the fake sheet is rich and when the changes come quickly. For pieces

where the harmony holds for the entire measure or longer, just playing the chords

will get boring. The first thing to try is to add bass notes to alternate with the

chords. In common time that would be note, chord, note chord. In three-quarter

time it would be note, chord, chord. One of the advantages of producing chords

high up on the left keyboard is to increase the distance between the chord and the

bass notes played as low as possible so that it more closely emulates stride piano

playing. This last technique is particularly effective on larger instruments.

Earlier, the 9th, 11th and 13ths were dropped in the interest of simplifying things.

However,

once the song has been learned, the player can consider adding some of these back

into his or her faked arrangements. This can be done with relative ease by using

the right hand when the melody movement (or lack of movement) allows the

freedom to add a note or two or even three. Frequently this can enhance a final

cadence of a piece, section or even a phrase.

Once one's fingers know these chords, they can be played as arpeggios. They may

also be played as arpeggios with bass notes. Playing around with these sort of

harmonic presentations can do much to add variety to ones playing. If you are

partial to traditional pieces these techniques and others will be helpful in adding

interest to songs with many verses. Other things to try could include playing the

melody in the bass with chords on the right, or nothing on the right or doubled in

the right. If you can sing the tune without the crutch of the melody doubled on the

concertina, you can play bass notes on the left with chords on the right. The idea

here is to make maximum use of these variations to keep things interesting for the

listener.

Putting Faking to Use

A benefit of learning to fake arrangements is that once done, it makes short work

of adding pieces to one's repertoire. This is particularly true if you do not object

to playing from the fake sheets. Simple tunes, some of which are very entertaining,

can be learned with just a few repetitions. Even tunes from say, the Cole Porter

Song Book, can be made presentable relatively quickly. That isn't to say that the

faked arrangements do not improve over time. Some of the mixing of different

faked techniques can be practiced when playing for oneself and then included in

performances later on.

Another point is that with modern computer and photocopying equipment, there is

no reason not to make a copy of each tune as you learn it. (You can usually fit an

entire tune on a single sheet if you copy the tune, cut out and discard the piano

part and tape the remainder on blank paper and recopy.) Nothing adds more to the

interest of a performance than a very large repertoire. This is especially true of

the player that often works with small intimate audiences where it is easy to see

what sort of song people like and customize the program on the fly. A large fake

book with tunes you have already played through and are familiar with is a great

tool if you can fake your way.

Kurt Braun

2004

Print Blank Charts

-

Blank Anglo Chords Chart

Blank Anglo Chords Chart

-

by Roger Digby

-

A single page with blank diagrams to note up to ten chords, containing spaces

for each chord name, buttons to use on push, and buttons to use on pull.

-

Posted 15 August 2005

-

» view or print chords chart in pdf

-

Blank Anglo Buttons-to-Staff Chart

Blank Anglo Buttons-to-Staff Chart

-

by Roger Digby

-

A single page with a blank diagram to relate buttons to notes on the musical staff.

-

Posted 15 August 2005

-

» view or print buttons-to-staff chart in pdf

Musical Examples to Accompany “Faking It”

-

“Faking It”: a dozen examples

“Faking It”: a dozen examples

-

by Roger Digby

-

Musical examples to accompany the web publication of “Faking It”.

Twelve tunes that are common in sessions and include most of the dance rhythms,

six tunes in C and six in G as the most common Anglo keys. Each tune is represented

by the music (printed without chords), and also by a sound file of Roger Digby

playing the Anglo concertina as you might hear at a casual session.

Originally presented at a workshop for the

East Anglian

Traditional Music Trust, 2004.

Tunes include: Blaydon Races, Dannish Waltz, Dorset Four Hand Reel,

Family Jig, Galopede, Greensleeves, Harry Cox’s Schottisch, Keel Row,

Shepton Mallet Hornpipe, The Man in the Moon, Three Around Three, and Winster Galop.

-

Posted 15 August 2005

-

» read full article

Author

Roger Digby

(

)

has an academic background in the Classics and Education and he

has spent his entire adult life teaching in the tough Comprehensive schools

of Inner-London Islington. This random move in the early 70s found him

living 100 yards from Crabb’s Liverpool Rd. workshop, close to some pubs

where the Irish music was the best in London and joining the company of

friends who in 1975 became ‘Flowers and Frolics’, a band at the sharp end of

what has become known as the English Country Music revival. They released

two influential vinyl LPs before calling it a day in 1985. A reunion in 1999

created a CD

‘Reformed Characters’ (available at www.danquinn.co.uk).

With ‘Flowers’ as resident band, Roger joined with singer Bob Davenport to

run the music nights at the Empress of Russia, a legendary music club which

was famously described by Melody Maker as the ‘most adventurous acoustic

venue in the country’. Bob and Roger still work as a duo and have released two

CDs (www.topicdrift.com/davenport).

Roger's most recent recordings are

included in the three CD compilation ‘Anglo International’

(available at www.angloconcertina.co.uk).

Roger has now moved ‘back home’ to his native North-East Essex where he

reads, gardens, walks his dogs, brews beer and enjoys retirement. He is

the Review Editor of

Papers of the International Concertina Association (PICA).